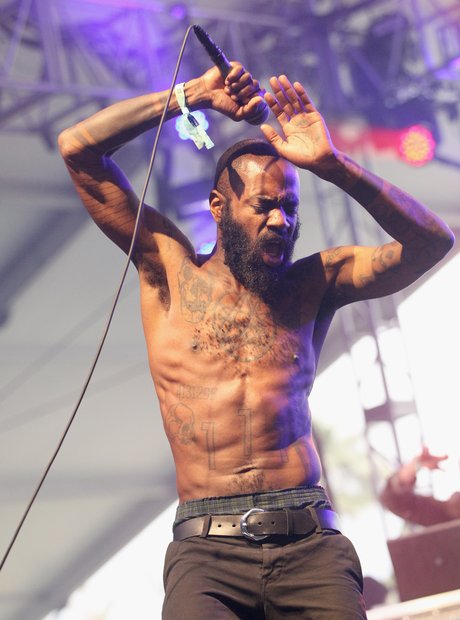

Shirtless, tattooed, and covered in sweat, his sinewy body commands a sea of young men to fanatically jump up and down to Death Grips’ “I’ve Seen Footage,” an aggressive, driving track off their seminal 2012 album, “The Money Store.” It’s a Tuesday evening, and the hypnotic Death Grips frontman is continuing their North America tour at the Warfield, a baroque concert venue in downtown San Francisco where thousands of true believers gathered to watch them perform underneath the delirious haze of red lights and weed smoke.

“I’m here for the ride, but I’m also dreading it,” said a man to his friend as he disappeared into the crowd. That evening, the venue was swarmed with demure goth guys in dog collars, skinny kids in True Religion, and e-girls in ghoulish clown makeup. Nearby, a security guard inspected a massive pile of confiscated wallet chains by the entrance. As I walked through the metal detector unscathed, I felt like Steve Buscemi in that famous meme from “30 Rock,” minus the skateboard and T-shirt.

It’s been about seven years since I’ve seen Death Grips live, and I suspect that the crowd, which was probably made up of teenagers and early twentysomethings, were drawn to them for the same reasons that I was.

Their sound — a toxic brew of rap, hardcore and abrasive electronica — has enraptured listeners for years, primarily because it eludes us at the same time. One thing that everyone can agree on, though, is that it is angry. Very angry. So angry, in fact, it even gave a California man the strength to obliterate Donald Trump’s Hollywood star with a pickax from Home Depot. In a 2012 interview with Clash, Death Grips described their creative process as grueling and masochistic, which was evident in their performance that evening. Even though they showed up to their sparse set an hour late, frontman Stefan Burnett, engineer Andy Morin, and drummer Zach Hill each played with fierce, single-minded intensity.

The group, too, gives little away, which only deepens their legend: There’s just a handful of decade-old interviews archived online, and the email address on their website seems to shepherd media requests into a bottomless void.

But in a rare 2012 interview with NME, the group — which is from “the dilapidated city of Sacramento,” according to the article — explained that social inequity is the driving force behind their raw, brutal sound. “We see desperation on a regular basis, every day, and we’ve been desperate ourselves,” Hill told the outlet. At the time, the British publication described California’s capital as a place where “horrific events” are a “day to day” occurrence and gang violence is rampant, though a walk through the city’s downtown corridor would make you think otherwise.

Against all odds, the group signed to Epic Records — a major label with a roster that includes “Jennifer Lopez, whoever wins The X Factor, and the Michael Jackson catalog,” according to Spin’s Christopher Weingarten.

“I was just sucked in. What I saw was a band that had the ability to capture violent, raw aggression in a way I hadn’t seen this decade. I couldn’t sleep that night. I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I was scared of them! I couldn’t resist the feeling of just wanting to be a part of it,” Angelica Cob-Baehler, Epic’s former executive vice president of marketing, told the outlet.

But not long after, the group firebombed their relationship with the label by leaking their album “No Love Deep Web” from their Chateau Marmont hotel room. Amid the fallout, they were dropped. Then, after they reportedly refused to play a Lollapalooza aftershow in Chicago, enraged fans wrecked their equipment, spurring more tour cancellations in Boston, New York and Canada. They’ve since formed their own record label, Third Worlds.

These days, anyone can download their discography for free on their website, and those who want to take it a step further can even claim the individual stems of drums, bass and vocals for “Guillotine,” or the instrumentals for scathing albums like “Government Plates.”

Though media outlets are fond of describing the group as ferocious, “aggressive” and mysterious, past interviews suggest that Death Grips actually lean into their own vulnerability. The small but catastrophic act of releasing their stems — which can be reappropriated and remixed to anyone’s liking — simultaneously encourages listeners to participate in their craft while exposing their desire to connect.

“When we play we like to welcome people to basically feel like they’re joining our group. Whoever’s in the room is part of the performance as well,” Hill told NME at the time. More than 10 years later, these words still seem to ring true.

That night at the Warfield, the crowd threw their arms around one another and screamed the lyrics to blistering tracks from “The Money Store,” “Exmilitary” and “No Love Deep Web.” As the energy peaked, MC Ride raised his arms like a maestro, while Morin, the group’s shadowy engineer, thrashed in the dark. Hill smashed cymbals, snares and toms with furious, unrelenting precision. Their collective noise flooded the sound system, washing over audience members, myself included, like some sort of primitive spell. Maybe the kids are all right.